For the next three weeks I’d like to share some observations from my academic research. I wish I could say I had good news, but to be honest I find the results quite sobering.

I study characteristics of societies using a technique called “agent-based modeling” (ABM). An agent-based model is a computational simulation of an abstract society of interacting virtual people, usually called agents. (When I say “abstract” society, I mean it’s not simulating any specific society — like France in the 15th century or Rwanda in 1990 — but more broadly any theoretical society of interacting agents.)

The agents are programmed to operate according to certain simple rules, usually simplified versions of how real humans actually operate. One goal of the research is to discover what large-scale societal effects would be produced as a natural result of individuals behaving in those ways. (Another goal is the converse: to test theories about how humans behave by verifying whether those behaviors would in fact produce societies with the properties we observe.) The results are often far from obvious.

For example, let’s say we postulate that each person has one of two possible opinions (their U.S. political party, perhaps) and that they communicate person-to-person via their existing social ties. Suppose further that every time person A initiates contact with a friend B, they are powerfully influenced by B to the point where they absorb B’s opinion as their own. (So if a random Democrat initiated contact with a friend who happened to be a Republican, a persuasive conversation would ensue in which the Democrat switched parties to become a Republican. If A and B were already of the same party, no change would occur.)

What would be the aggregate result of this?

It might astonish you, as it certainly did me, to learn that the inevitable result of this set of rules is complete uniformity; i.e., a society of either all Democrats or all Republicans. The two factions do not, as might be supposed, grow and shrink in perpetuity as each strives for dominance in a never-ending struggle. The animation below shows one such society, in which red turns out to be the winner after 106 interactions.

Now the fact that in real societies we normally don’t see this collapse to uniformity tells us something: the model is wrong, or at least inadequate. Real people obviously do not act in exactly this way, because the society produced by such an assumption contradicts what we actually see. And from there a whole branch of inquiry begins, in which we could investigate what sorts of tweaks to the individual rules of behavior might lead to a more empirically valid outcome. It’s a large branch; I’ve spent years on it.

But I now want to pivot slightly to make my point for today. Let’s consider why the “I will copy your opinion when I encounter you” rule made any sense to try in the first place. It’s because this is an example of the principle of homophily (pronounced huh-MOFF-uh-lee) which governs so much of human behavior.

Homophily is the rather mundane observation that we tend to love (“phil-“) those who are similar (“homo-“) to us. In our dealings with other people, we very often want to (a) change them to be similar to us in some way, or (b) change ourselves to be more similar to them, or simply (c) seek out people who are already similar to us in the first place. The “similarity” can be on any axis: gender, age, race, geographic origin, political affiliation, favorite football team, etc. Phrased more negatively, we seem to be uncomfortable being around people who are different than us.

I used the word “tyranny” in the title of this post because homophily seems to me absolutely despotic. It is the dominant factor in nearly all human relations. Who do we want to marry? Someone just like us. Who do we want to be friends with? People like us. Where do we want to settle? In a neighborhood full of people like us. Where do we want to sit in the cafeteria? Near others who are just like us.

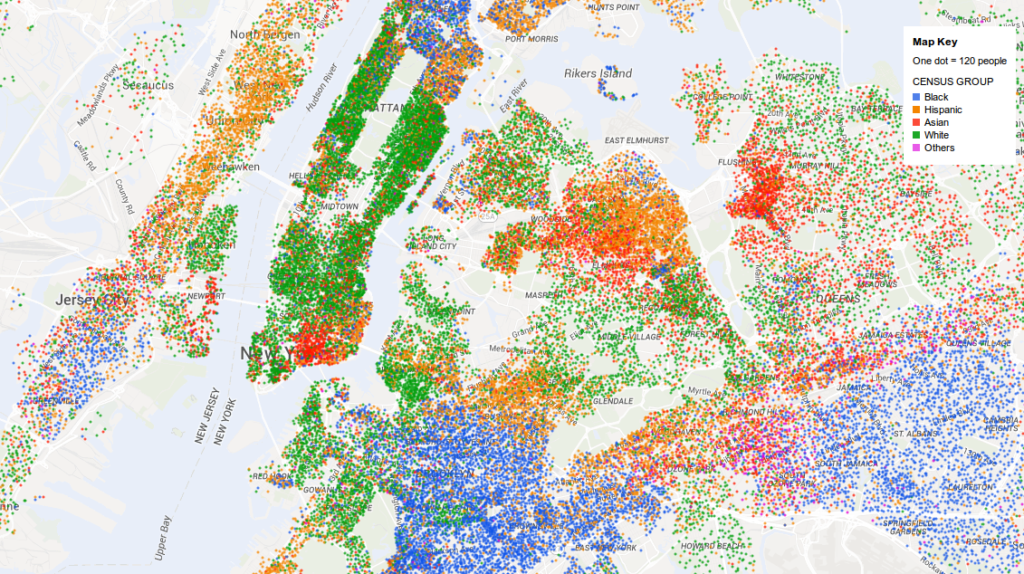

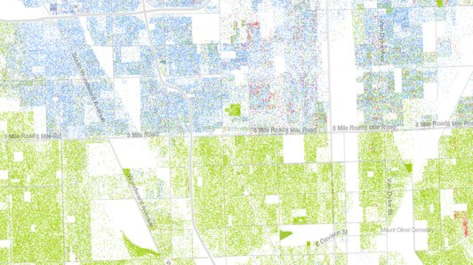

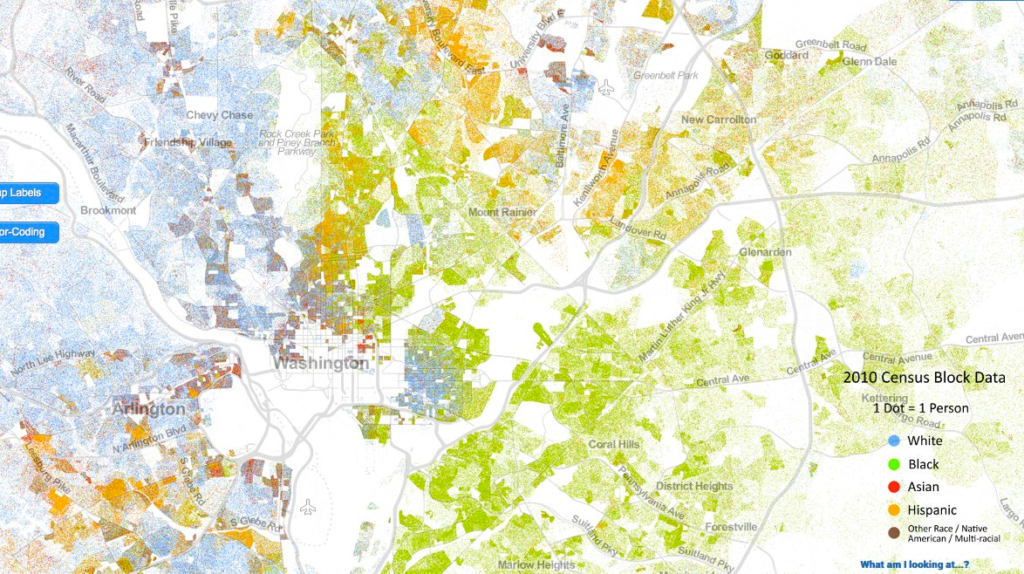

It’s the reason that if you look at an aerial view of nearly any large city, color coded by census tract, you will see all the inhabitants tightly clustered by race:

It’s the reason that within the first five minutes of a social gathering, you will almost surely see all the women clustered up and talking together, and all the men in a separate group.

It’s the reason that on any playground, the jocks will all find each other, the goths will all find each other, the “cool kids” will all find each other, and the nerds will all find each other. From that point on, they might as well be on separate planets.

And it’s the reason that nearly all of a person’s friends have the same political opinions that they do, even though they may live right in the midst of many who have opposite views.

That last example turns out to have a curious side effect, which I’ll address in next week’s post. My students (Justin Mittereder and Harmony Peura) and I call it issue entanglement (IE) and you might be able to guess what it is just from the name. But without giving too much away, I’ll just say that it’s a good explanation for a phenomenon I’ve found puzzling since childhood: the fact that strong correlations exist between people’s opinions on seemingly unrelated issues. Tell me someone’s stance on abortion, and I’ll bet I can tell you with near pinpoint accuracy where they stood on mask mandates in 2020, or on delivering military aid to Ukraine today. I think you’ll agree that’s pretty strange on the surface of it, considering that life’s origins presumably have nothing to do with virus transmission or foreign wars.

But that’s too many spoilers already. Until then, I’ll just leave you with this question: how much of a role does homophily play in your own life? How many of the friends, activities, and even opinions you choose are at least partially dictated by wanting to be surrounded by similarity? If I’m honest, I’m afraid my own answer to that question is pretty depressing.

— S

Leave a Reply