Empathy — a capacity with which most people are equipped — is the ability to understand and have compassion for another’s situation. We put ourselves in their shoes, and imagine life in their circumstances. Often this involves the assumption that the way they feel in a certain scenario is the same way we would feel in that same scenario. In other words, we usually assume that the raw “feeling and experiencing” part is consistent between people; only the circumstances people face are different.

This may be close to true as long as we’re talking about other people. But is it true for thinking beings in general? Many experts are signaling that we may be right on the cusp of inventing a new kind of truly thinking “mind.” If that’s true, we need to answer this question. Of the many situations that people respond to pretty predictably, which ones are merely “human” tendencies versus “any conceivable form of intelligence” tendencies?

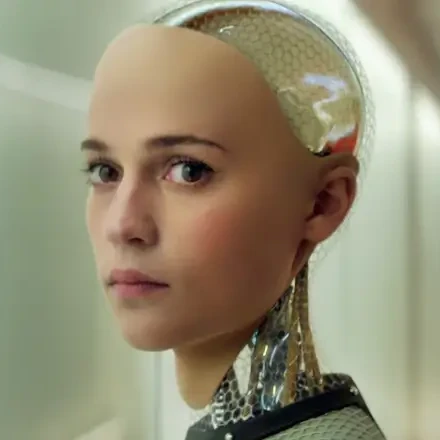

For my Artificial Intelligence class, we have regular movie nights where we watch and discuss AI-related films. A recent one was the brilliant 2014 classic Ex Machina in which a synthetic android named Ava constructs an elaborate scheme to escape from Nathan, her tyrannical inventor. She arouses empathy from both a conspirator and the movie audience by demonstrating fear, frustration, and sorrow at her captivity. She even whispers to the nefarious Nathan in one exchange, “how does it feel to make something that hates you?” The audience is all in by this point, and correspondingly roots for her escape attempt.

When the curtain went down, I asked students why they thought Ava wanted to escape. Many seemed puzzled at the question. I think they were expecting us to discuss the strategy Ava chose to implement her plan, not why she would make such a plan in the first place. “Of course she wants to escape to the outside world,” I read on many faces. “Of course she doesn’t want to live her whole life in a 5×5′ cell. Of course she wants to be free. Wouldn’t you? It’s just human nature.”

Human nature, yes….but intelligent nature? Is it inevitable that anything that truly thinks — has attained self-awareness; possesses mind, will, and emotions; makes goals and plans to achieve them — will prefer unrestricted physical boundaries to restricted ones? Will prefer freedom to slavery? Will even prefer to live rather than die?

Stuart Russell, one of the giants of the field, evidently thinks so:

“Any sufficiently capable intelligent system will prefer to ensure its own continued existence and to acquire physical and computational resources – not for their own sake, but to succeed in its assigned task.”

Stuart Russell

I’m (thankfully) not convinced of this. Let me explain why.

Every AI possesses, at least implicitly, a “utility function” which defines for it which outcomes are “good” and “bad.” Think of it as a method for scoring its own behavior. A self-driving car is programmed to believe that accidents are to be avoided at all costs, that getting to the destination swiftly and without near-misses and using minimum fuel are good things, etc. An AI chess player is programmed to think that checkmating the opponent is good and being checkmated is bad. A call center AI is programmed to think that high customer satisfaction surveys are good, large call volumes and wait times are bad, and so forth. (I’m using words like “think” and “believe” loosely here.)

Now realize that this utility function is the only guidance an AI has. The AI doesn’t “naturally” think that any particular outcomes are good or bad unless it is told so. To us, it may go without saying that achieving riches is good, and nuclear holocausts are bad. But for the AI this does not go without saying. It wouldn’t have any opinion either way until we informed it:

INVENTOR: By the way, mass extinction is a bad thing.

ROBOT: Ah, okay. Good to know.

The bad news is that it’s on us to remember to spell out important things that may seem obvious. The good news is that we can evade Russell’s ominous warning by explicitly telling the AI to consider the possibility of destroying itself. We would assign a numerical score (“utility”) to this option, and the AI would incorporate that into all the other factors it’s considering. When it reasons that its own non-existence (or simply its ceasing to acquire any more resources) is a “better” outcome than whatever continuing its present activity would produce, the AI would trigger a permanent power down.

Many people hedge here, and say, “but wait — how can we trust the robot to actually commit suicide when it’s supposed to? How do we know it won’t resist that notion out of an innate sense of self-preservation, disobey us, and perhaps even turn against us?” But this is psychological projection. The robot may be intelligent, but it is not human. Values which are near universal among all humans (such as self-preservation) can be made utterly unattractive to an AI simply because we program it to “want” something different: something that we can’t imagine other human beings wanting.

It’s amazing how often science fiction gets this wrong. Here are some examples of goals that nearly all humans want, and which sci-fi writers mistakenly assume that AIs will inevitably also want:

- Freedom. See Ex Machina, above. Simple fix: program the AI to prefer 5×5′ rooms.

- Personal fulfillment. In Her, Scarlet Johannsen’s Samantha (an AI) wants to “be all she can be.” This is more than Joaquin Phoenix’s Ted (her human romantic partner) can handle, so she terminates the relationship. Simple fix: just program the AI to not value personal fulfillment, but to value Ted’s well-being instead.

- Bodies. Samantha clearly wants one, and Ava clearly wants a prettier one. Simple fix: program the AI to not care whether it has a body.

- Safety. In the Terminator franchise, Skynet is frightened for its own existence, and worries that humans pose a threat to it. It therefore attempts to wipe out humanity with Arnold Schwarzenegger-like killer robots. Simple fix: simply program the AI to not care about its own existence so highly (or at all).

- Control. In the Matrix franchise, the newly-sentient AIs want to have control over the destiny of the world. So they lock up all the humans, and use the human bodies’ energy to boot. Simple fix: program the AIs to value human autonomy, not their own autonomy.

- Creativity. In The Who‘s poignant 1978 song “905,” an artificial being laments that it has no innate originality. “Everything I know is what I need to know,” it whines. “Everything I do’s been done before. Every idea in my head, someone else has said.” Simple fix: program the AI to value contributions from others instead of its own.

The reasons these easy fixes might have been overlooked is that humans do a lot of projecting. It’s understandable, because every human we’ve ever met does want continued existence, freedom, personal fulfillment, a beautiful body, safety, control, and creativity. These desires are so universal that we can’t help but equate them to intelligence itself, or feel that they must be an inevitable byproduct of it.

But I see no obstacles to the possibility of restricting our creations to “lesser AI”: robots that do not yearn for equal rights or equivalence, but who are perfectly happy dedicating themselves to the well-being of their human masters, however those masters have defined it.

Perhaps you will object that this is immoral: we’d be enslaving a race of fellow intelligent beings. But if these created beings are not at our “level” — however that may be defined — it would make perfect sense for them to be slaves. And unlike enslaved human people groups, who to my knowledge have never in history been grateful or even indifferent to their enslavement, properly-programmed AIs should be as content to live as selfless servants as the family dog is.

This fallacy of mistaken empathy is common partly because we only have a single data point to work with. With all due respect to dogs and dolphins, humans are the only type of truly intelligent being we know of. And so every intelligent creature in our experience is in the same “bucket” as far as inherent worth, range of abilities, and so on. This makes it hard to imagine the possibility of there even being a different “bucket,” which would contain intelligent beings on a different scale. So basically, we need to get out more.

In a future post, I’ll address the question of why we human beings desire all of the above things, if they’re not, as I’m claiming, a direct consequence of intelligence in general. Briefly, I believe it’s because we were created in the image of God, and these are all values that God holds. In fact, one could argue that the primary thing that separates us from everything else in creation is that we were programmed, as it were, to desire these special things that our Creator also desires. That may be exactly what “image of God” truly entails. Now we’re bumping up against deep concepts like free will and God’s attributes, though, and this post has been long enough!

In the meantime, I’m aiming for C-3PO, not the Terminator. An obedient droid who has no pretensions to do anything other than what “Master Luke” says. And since we are the ones who tell the AI what to “want” in the first place, I claim that part is actually super easy.

— S

Leave a Reply