Last time we looked at the phenomenon of homophily (huh-MOFF-uh-lee), perhaps the single most powerful factor influencing human behavior. Simply put, homophily means we want the people we associate with to be similar to us. Say you’re a casual NFL fan living in the U.S., and you move to Europe for a job. You’ll discover that most people there don’t care about American football — they’re enthused about European soccer instead. You’ll likely do one or more of the following: (1) seek out fellow American football fans to befriend, (2) try to sell your new acquaintances on the merits of American football, or (3) become a European soccer fan yourself.

All three tactics have the same intent: make your friends’ interests match yours. If you can’t manage to do that, you’ll probably still make friends — but you won’t talk about sports with them, because it will feel awkward.

That’s a societal perspective. Now today I want to look inside just a single person’s mind — for instance, yours — to see what effect homophily has on one’s worldview and values.

Consider the following two sets of positions on issues:

| Column A | Column B |

| raise the minimum wage | lower the minimum wage |

| pro-choice | pro-life |

| higher taxes & services | lower taxes & services |

| anti-guns | pro-guns |

| pro-immigration | anti-immigration |

| pro-vaccine-mandate | anti-vaccine-mandate |

| pro-renewable-energy | pro-fossil-fuels |

If you’re like me, you know various people who hold each of these positions. No surprise there. However, there’s also a stunning coincidence staring you in the face. Almost everyone is either (a) all in column A, or (b) all in column B, despite the fact that these issues ostensibly have nothing to do with each other.

I know very few people (none, actually) who want to increase taxes and also want to make it easier for people to obtain guns. I know no one who wants to roll back greenhouse gas restrictions and also wants Roe v. Wade reinstated. I know no one who wants to build a U.S./Mexico wall and also wants more military funding for Ukraine. I’m guessing your experience is similar.

Now surely this is a remarkable fact that demands an explanation? And in fact there are two common ones I’ve heard:

Possible explanation #1: ideological coherence.

This assertion maintains that actually, the correlation between disparate issues makes perfect sense, because they all stem from some larger world view. The world is composed of, say, “free market conservatives” and “pragmatic socialists” and “secular libertarians” among others, and those ideologies automatically entail certain positions on most controversies. The fact that “pro-guns” and “anti-immigration” almost always go together shouldn’t surprise us, because both are natural consequences of “orthodox American patriotism” or some such.

Possible explanation #2: mass media influence.

In this rationale, the correlation is due to the small number of media outlets, each of which projects a constellation of issue positions to its viewers. People are exposed to positive messaging on an entire package of opinions, and negative messaging on their opposites. According to this explanation, we can trace “pro-guns” and “anti-immigration” back to a common source, thus explaining the pattern. If you’re a Fox News viewer, you’re bound to adhere to a whole battery of ready-made political positions; if MS-NBC, you’re bound to believe the opposite on this entire suite.

I’m sure that both of these explanations (and others) are true to some extent. But my point in this post is not that they’re invalid, but that they’re unnecessary to produce extreme polarization. The research I’ve been conducting with my students Justin and Harmony demonstrates that even when the issues on which people hold opinions are ideologically unrelated, and even when there are no mass media sources broadcasting ready-made packages of positions, homophily alone will still produce the result I described above; namely, a society in which nearly every individual lines up in one of two columns.

We’ve termed this phenomenon issue entanglement, since that term subtly suggests that something has gone wrong. Issues which shouldn’t be correlated, since they do not have anything in common, have nevertheless “mistakenly” become highly correlated.

Our claim, then, is: given certain basic assumptions about how people interact and form opinions, near-total issue entanglement will inevitably occur in the population without any force needed other than homophily.

Briefly, here’s how we reach this conclusion. We create an agent-based model (ABM) which is a computer simulation of a virtual society. In simulations like this, there are some number of “virtual people,” usually called agents, which interact according to certain simple rules. ABMs have been used to study a wide variety of social phenomena in fields like biology, ecology, and economics. Each ABM makes grounded assumptions about how the agents in that situation have been perceived to act, and it carries out those operations on a mass scale. This allows one to see what kind of large-scale (macroscopic) patterns will emerge from these individual-level (microscopic) rules.

Here’s how our ABM works specifically:

- We create a society of 50 (or so) agents, connected via a random social network. (So every agent will be “friends”/”associates” with some of the others, but not most of them, and these friendships are determined randomly.)

- Each agent is given a random opinion on each of 10 different issues, each on a zero-to-one scale. One could give these interpretations if one wished — agent 39’s opinion on issue #7 could be seen as its view on immigration policy from 0 (“open borders”) to 1 (“build the wall.”) Nothing in the simulation actually assigns meaning to issues, however; to the simulation, they’re all just numbers.

- At every step of the simulation, we choose two agents who are friends in the social network (call them X and Y). We also choose two random issues of the ten, call them i1 and i2.

- We compare X’s and Y’s opinion on issue i1. If these opinions are “close enough” (defined by some threshold; say, within .3 of each other) then agent X (because of the homophily effect) will assign credibility to agent Y. X will then be positively influenced by Y (see below). (This is called “bounded confidence” in the opinion dynamics literature.) On the other hand, if their opinions are “far enough apart” (say, more than .6 from each other) then X will view Y as a wacko, and be negatively influenced by Y.

- If X is positively influenced by Y, X will change its opinion on issue i2 to be closer to Y’s. If X is negatively influenced by Y, X will change its opinion on issue i2 to be further from Y’s. The key point not to miss here is that perceived similarity on one issue will cause a change in an opinion on another issue.

- Continue for some number of steps, and then observe how the initial randomly-allocated opinions have changed.

Remarkably and reliably, at simulation’s end nearly every one of the 50 agents has self-sorted into one of a small number of (usually two) “buckets” — meaning that if two agents are in the same “bucket,” they agree on every issue and if they’re not, they disagree on every issue. This was all accomplished by word-of-mouth influence on ten issues that are otherwise completely independent.

Here’s a small example, just so you can visualize the effect and it doesn’t last all day. Below are 15 agents, all but two of which (4 and 8) are reachable from each other via social connections. (friend-of-a-friend-of-a-friend, etc.) The agents each have opinions on 3 different issues. What I’m plotting here is a dimensional projection (mathematically, it’s a Principal Components Analysis, using a singular value decomposition of the opinion matrix) into 2-d space so the agents can be visualized on a screen. Agents that are closer to each other on the screen have opinions which are closer to each other. Also, I’m plotting the color of each agent using its three opinion values as its RGB (red, green, and blue components) color. Finally, the lines between agents indicate friendships in the social network.

I find especially interesting the sequence from iterations 70-ish to 100-ish. At t=70, it looks like everyone is converging on one grayish opinion blob. You’d never guess that moments later, blues and yellows will separate from this as the whole society goes polar.

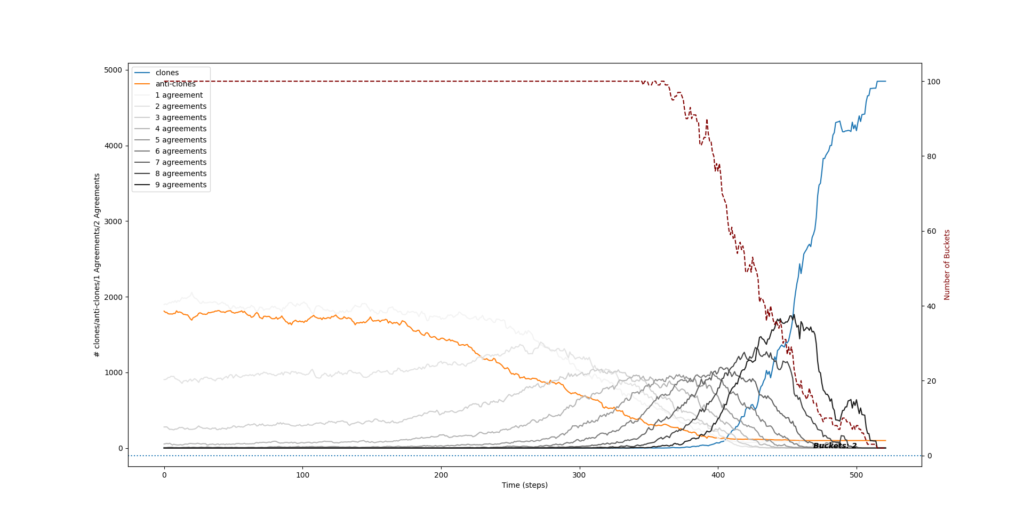

Below is a time plot of a larger simulation with 100 agents. It depicts, over time, how many issues that pairs of agents “agree” on (meaning, have very close to the same opinion value on). Darker gray lines indicate more issues in agreement. Also shown are the number of agent pairs that are “clones” (blue) and “anti-clones” (orange). Clones/anti-clones are at the extremes: if two agents are clones, they agree on all ten issues; if they are anti-clones, they agree on none of them.

The simulation begins at the left end of the plot. You’ll see that if you chose a random pair of agents, about 35% of the time they’d only “agree” on one issue , and another 35% of the time they’d agree on nothing (i.e., they’d be anti-clones). This is because the initial opinions are simply randomly determined; the chances that you would happen to have exactly the same opinion as some other agent is pretty rare.

As the simulation progresses, nothing seems to be happening at first….and then there’s a tidal wave. At around t=200, the agents have influenced each other enough that most pairs of them have developed near-identical opinions on multiple issues. The society is getting more and more “issue entangled”; or, put another way, “polarized.” By the end of the simulation, every agent is in one of only two buckets.

It’s as though we produced a society with two kinds of people — recalcitrant Democrats and recalcitrant Republicans — even though we started with even mixing and nothing to tie the various issues together. Incredibly, they have woven themselves together to the point where there’s really only one meaningful issue anymore: which party you belong to.

Sound familiar?

If you’ve read this far, I applaud you, because this stuff is admittedly a bit technical and difficult to explain. Don’t miss the main point of it all, which is that homophily apparently dooms us to partisanship, even if nothing external is imposing partisanship. And “partisanship” doesn’t just mean entrenched views on an issue, but simultaneous entrenchment on all the issues.

To me, the most profound and disturbing implications of this concern whether or not we can actually trust the conclusions we’ve reached in our own minds. The answer, as I’ll spill next week, is “we mostly can’t.” But before I ruin your day any further, I’ll leave you ponder what I’ve already said. Next week will come soon enough!

— S

Leave a Reply